Cash transfers to women have gone from 1 to 15 states in 5 yrs | India News

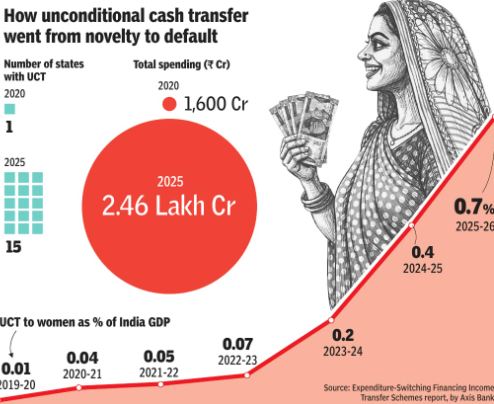

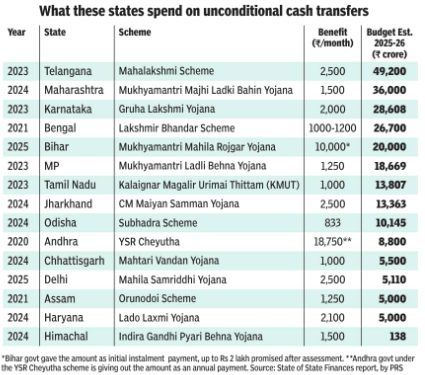

From one state in 2020 to 15 states today, unconditional cash transfers (UCT) to women have gone from a political novelty to a full-blown welfare pillar. The annual outlay has exploded from Rs 1,600 crore (2020) to Rs 2.46 lakh crore (2025) — a jump so large it now rivals the biggest social-sector commitments in the country. Together, states are set to transfer this money to roughly 13 crore women in FY26 — about a fifth of India’s women — turning “cash in her account” into a standard election promise, and a real budget constraint.That’s the new arithmetic of Indian welfare: direct money to women, designed with poll-time gains in mind, but producing effects that extend beyond votes — in household spending, women’s bargaining power, and state finances.

Women in Maharashtra show phone alerts of cash being credited under Ladki Bahin scheme

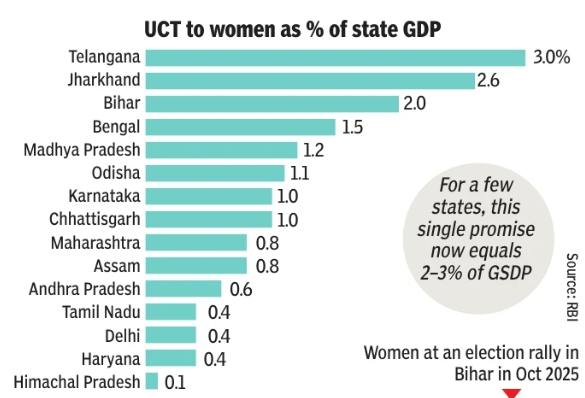

1 Big Outlay, Bigger StrainCash transfers are funded through state budgets and, in a few states, the spending on women’s UCT now runs into 2-3% of gross state domestic product (GSDP). Several are also running revenue deficits, and analyses suggest their fiscal position looks materially better if these schemes are taken off the books.

The trade-off is blunt: every extra rupee committed here is a rupee harder to deploy elsewhere — health facilities, nutrition programmes, school infrastructure — unless the deficit widens.Yet, states keep expanding them because the payout is visible, measurable, and politically profitable. Dictated by the need to cater specifically to women voters beyond the promises of ‘ bijli, sadak, makaan, pani ’, these cash transfers are targeted towards what is being seen as a new voting bloc in Indian electoral politics.

.

2 Targeted Schemes, Tailored PoliticsThe design varies sharply across states — from Rs 2,500 a month in places like Telangana, Jharkhand and Delhi (as promised) to annual or one-time payouts in Bihar and Andhra Pradesh. Eligibility rules also swing widely: some target married women within income limits, others include widows/single women, and a few are inching toward near-universal adult coverage.The result is an arms race across parties and states: whoever governs, a women-focused cash transfer is increasingly treated as baseline.

.

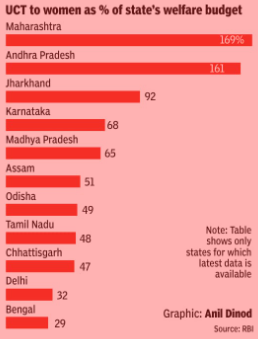

3 UCTs Dominate Welfare BudgetIn Maharashtra, allocation for the Ladki Bahin scheme is over 1.5 times the total spend on welfare. It’s the same for Andhra Pradesh.

.

For most states, each extra rupee that goes into UCTs can bear heavily on the budget, meaning that they cannot think of expanding health infrastructure or deepening nutrition programmes without pushing deficits even higher.

.

Yet, govts seem to be signalling that predictable, liquid cash in women’s hands is worth this opportunity cost. Some states have now trimmed or frozen hikes in other welfare items while sharply ramping up UCT allocations, effectively re-prioritising towards one flagship promise that is visible, measurable, and promises electoral dividends.

Women at an election rally in Bihar in October 2025

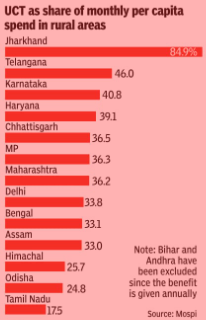

4 Transfers Now A Chunk Of Family BudgetPopulist cash transfer schemes may put state balance sheets under pressure, but experts say the fiscal burden must be weighed against the need to address entrenched gender inequality.Sunaina Kumar, who leads the development centre at think tank Observer Research Foundation, says, “The amounts are very modest and, even then, they do make an impact on women’s rights. A large section of women is out of work and faces absolute economic marginalisation. In that context, these programmes are responding to that need. It is kind of like a short-term approach, but I think we do see positive impacts.”The latest Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) puts average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) at Rs 4,122 in rural and Rs 6,996 in urban India. For low-income households — where per capita spending may be closer to or even below that — a transfer of Rs 1,000-Rs 2,500 per woman every month is far from trivial. It can represent a good fraction of what a person might otherwise consume in a month.

.

5 Where Is The Money Spent?The spending pattern across multiple state studies is strikingly consistent: this money doesn’t usually become discretionary splurge — it becomes household glue.● Food tops the list (e.g., 53% in Maharashtra; 78% in Karnataka; 43% in Tamil Nadu overall).● Health/medicines and children’s education/fees come next in many places.● Utilities/LPG show up as a regular claim on the transfer.● A meaningful minority save part of it, and some use it for small productive spends (livestock, farm inputs, microenterprise goods).● It also goes into debt repayment, but generally as a smaller share.Source: Project Deep, state govt reports.